Teaching about ancient Sparta is always a challenge. It was certainly a very unusual city-state in ancient Greece, but the extent of its strangeness is often over-stated. Movies such as 300 (Zack Snyder, 2006) popularized the idea of the Spartans as fearless, physically perfect killing machines, but the myth of Spartan invincibility already existed in the fifth century BC, and even then it was only a myth. It was the first Greek state we know of to adopt an organized system for the military training of its citizens, and this meant their army tended to be a bit better than the armies of other states, and in hand-to-hand combat, being a bit better was actually a very big advantage. Yet the Spartans also had several losses in their history: their mass surrender to Athenians forces on Sphacteria was particularly memorable, and Athenian aristocrats expressed their opinion that enslaved Spartans made the best nurses. Scholars frequently write about the ‘Spartan myth’, which makes it difficult to truly understand that famous city-state.

The problem is that most of what we know about Sparta at its height comes from hostile sources, especially Athens, which was engaged in on-again off-again conflicts with Sparta for the latter half of the fifth century BC. Many wealthy Athenians disliked their own native democracy and instead lionized Sparta’s oligarchy, whereas comedians tended to make Spartans look ridiculous to delight Athenian audiences in wartime. So it is dangerous to fully trust Athenians sources on Sparta. Our other great source of information on Sparta are the writings of the Greek author Plutarch, who lived in the Roman Empire more than 400 years after Sparta had been crushed by the might of Macedon. In Plutarch’s lifetime, the Spartans relied heavily on Roman tourism to support their economy, and so they no doubt told many amazing and even strange tales about their glorious ancestors to delight wealthy Roman visitors. So whenever my university courses move onto the Spartans, I start by warning my students about the challenges we face in evaluating the evidence we have. How do we assess the sources and determine what to believe?

Nowhere is that more true than with tales of Spartan women. We must always keep in mind that ancient, male-dominated societies often used descriptions of the treatment of women to define themselves and others. Greek men defined their own themselves (in part) by the way they treated their women and by the roles and activities their women were permitted to have in their society. So one way for a group to distinguished its own society from others was to differentiate their treatment of women, as if to say: “our women hold the proper roles and status in our society, so we can judge other societies (in part) by the degree to which their women either resemble or differ from our women.” So claiming that the women of a rival state were morally bad was a convenient way to suggest that the men of that state must also be morally bad. Nowhere is this more obvious than in tales of the Amazons, whom Greek authors presented as being so ‘backward’ that women ruled and fought in battle, while their men were relatively powerless and weak. That is, tales of the Amazons were intended to express a society very much the opposite of Greek society, and that was achieved by presenting the behavior of Amazonian women as the opposite of Greek women. Hence, a Greek hearing the story was to understand that Amazonian society was bad and backwards because the women did not act like Greek women.

As noted above, ancient sources (especially those from Athens) often viewed the Spartans as being different and even ‘the other’, and a convenient way to express that was telling fantastic stories of Spartan women that made them appear the opposite of Athenian women. In other words, an easy way for an Athenian author to denigrate the Spartans was to tell stories that portrayed the behavior of their women as being different from that of Athenian women. Such use of female behavior could also be used among the Athenians themselves to criticize their own behavior: the Athenian comic playwright Aristophanes was so exasperated with the reckless decisions of his fellow male citizens in their war against the Spartans that he wrote several plays in which Athenian women take charge of the state and make things better. He presents the women defeating the men in fights or tricking them through superior cunning and intelligence, and in this way they seize power and run the state better than the men (Aristophanes’ targets for criticism) ever did. It was his way of saying that the deviant behavior of the women demonstrated that Athenian men had become worse than women (he did not intend it as a compliment to either group!). So ancient stories about female behavior were sometimes (not always!) used to define the men in their society.

This does not mean the stories of Spartan women were necessarily false, but it does mean we need to pay close attention. For example, Plutarch tells us that on Spartan wedding nights, the bride’s hair was cut short, she was dressed in male clothing, and she was placed in the groom’s bed with the lights out to await her new husband’s arrival. The implication is that, prepared in this way and with the lights out, the young bride might easily be mistaken for a young boy. Is this an accurate account of Spartan wedding practices, or was it a (perhaps Athenian) tale intended to suggest that Spartan men preferred sleeping with boys? Should we use stories like this to reconstruct Spartan society, or should we consider that it may have been an Athenian insult or piece of negative propaganda? Caution and circumspection is needed!

Thus forewarned, let us examine the stories of Spartan women engaging in physical exercise. Again according to Plutarch, Spartan girls were—contrary to general Greek practice—expected to engage in public exercise, just like Spartan boys. This would have been surprising to other Greeks not only because it put those girls on public display (a thing that rarely happened outside of certain religious festivals), but also because people in the ancient world exercised nude (there were no sweatsuits or easily cleaned clothing to wear while working out under the hot Greek sun!). Indeed, the place in any Greek city-state where citizens went to exercise was the gymnasium—literally, the ‘naked place’ (from the Greek work γυμνός/gymnos for ‘naked’). While it was considered manly and virtuous for any Greek man to strip naked and exercise publicly, the idea of a Greek woman from a respectable citizen family doing the same was practically unthinkable. Indeed, it was perilously close to the situation of enslaved women who were forced into sex work, whose naked bodies were often displayed openly by those who profited off them. Indeed, women were expected to be fully clothed even in statuary: Greek sculptors often made statues of naked men, but women were presented as clothed until Praxiteles made the famous nude statue of Aphrodite called the ‘Aphrodite of Knidos’ in the fourth century BC. So the idea that Spartan girls would exercise naked in full view of the community was shocking and even scandalous.

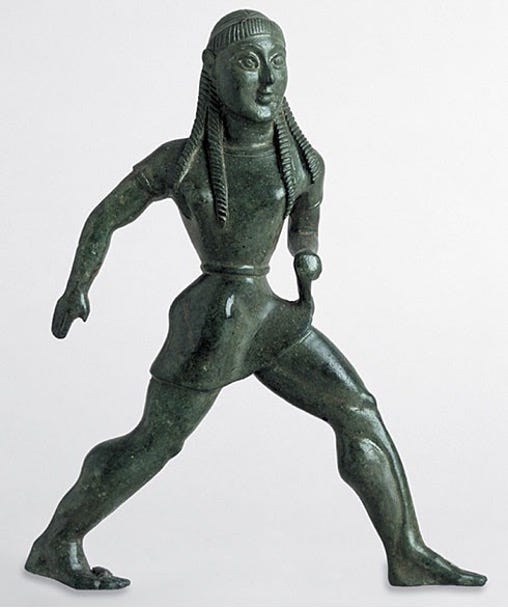

Did the Spartans really have their young women exercise naked in public? The evidence is not clear. On the one hand, in two of his works Plutarch writes that Spartan girls exercised strenuously just like boys, although he does not specifically say they were naked as the boys would have been. On the other hand, he also writes that the unmarried Spartan girls regularly walked nude in public processions just as boys did, so that they would learn to appreciate their physical strength and not be ashamed of their bodies, and he also says that girls (like boys) only wore tunics when partaking in certain processions (suggesting they were often nude in public). On the other hand, bronze statues of young Spartan women dressed in short skirts (appropriate for running) have been discovered by archaeologists (see above and below), and they may have originated in Sparta, which would be strong evidence that women did not exercise naked, but in lighter clothing that allowed free movement, perhaps similar to the shorter dress often worn in artistic depictions of the young goddess Artemis, the patron goddess of Sparta. On yet another hand, Greek pottery—perhaps Athenian—has been discovered that seems to portray Spartan girls exercising naked, but since such images appeared on fine wares (that is, expensive), it is perhaps likely that such images were intended for men’s drinking parties, and so the pottery was intended to present sexualized images of Spartan girls for male consumption, rather than be an accurate representation of Spartan practices.

On balance, the statues of (lightly) clothed female Spartan athletes are perhaps better evidence of Spartan practices, and the pottery portraying them nude represented Athenian (or at least non-Spartan) fetishizing of Spartan women. But both support the point made by Plutarch that young Spartan women did—contrary to Greek custom—exercise publicly. He explained that Sparta’s famous lawgiver Lycurgus set down this custom so that Spartan women would have healthy minds and bodies just like Spartan men. This does not appear to have been wholly altruistic, however, since Lycurgus is said to have done this to ensure that the superior health of Spartan women would enable them to have babies of superior health (child mortality being frighteningly high in the ancient world). So the prioritization of female health in Sparta was (according to our sources) done to ensure the steady production of healthy babies, who would grow to serve in Sparta’s army and produce more healthy babies to ensure the future of the state. This may be supported by another detail: our sources say that girls in Sparta usually married a little later than girls did in the rest of Greece. In Athens and elsewhere, it was usual for girls to be married and start producing children as young as 14 or 15 years old—the medical writings in the Hippocratic corpus recommend marriage and pregnancy as soon as a girl is going through puberty. In Sparta, however, girls seem to have gotten married around age 18 or 19, perhaps because experience taught them that this could improve newborn health. So the Spartans appear to have been concerned about women’s health on some level, even if it was mainly to ensure stronger children for the state. So it would indeed appear to be the case that Spartan women were remarkable because—unlike other Greek women—they were expected to exercise strenuously in public, just like Spartan men.

One final element about the exercise of Spartan women deserves special comment. In the same paragraph in which he described Spartan girls exercising, Plutarch also writes that groups of them would also observe the boys as their trained or otherwise moved about in public. When the troupe of girls saw a boy with a good reputation for his deeds, they would together sing a short song praising his bravery, strength, or accomplishment, thereby publicly acknowledging and rewarding the boy’s excellence. When they came upon a boy who had a reputation for misbehaving, however, the girls would mock and ridicule him, again publicly. Thus in addition to exercising their bodies, these groups of girls performed an important job for their state by reinforcing communal values in the boys by praising those who excelled in those values while taunting those who fell short (Degas produces a famous painting of this type of social reinforcement).

There is so much more that can be said about Spartan women, but they are an excellent example of why we must always be very careful about how we approach and read evidence. Some of what was said about Spartan women was probably not true, but was instead propaganda made up by those hostile to Sparta who wanted to denigrate Spartan men by sensationalizing their women. On the other hand, it is clear that Sparta’s women were exceptional in many ways, and that their roles in their society were acknowledged in ways that other Greeks would have found strange.

This is really fascinating. What led

You to write this article ? Seems like an odd subject at first but was really interesting. Not something I’ve ever thought about. Society back then would seem so foreign to us now