Sparta’s Achilles Heel

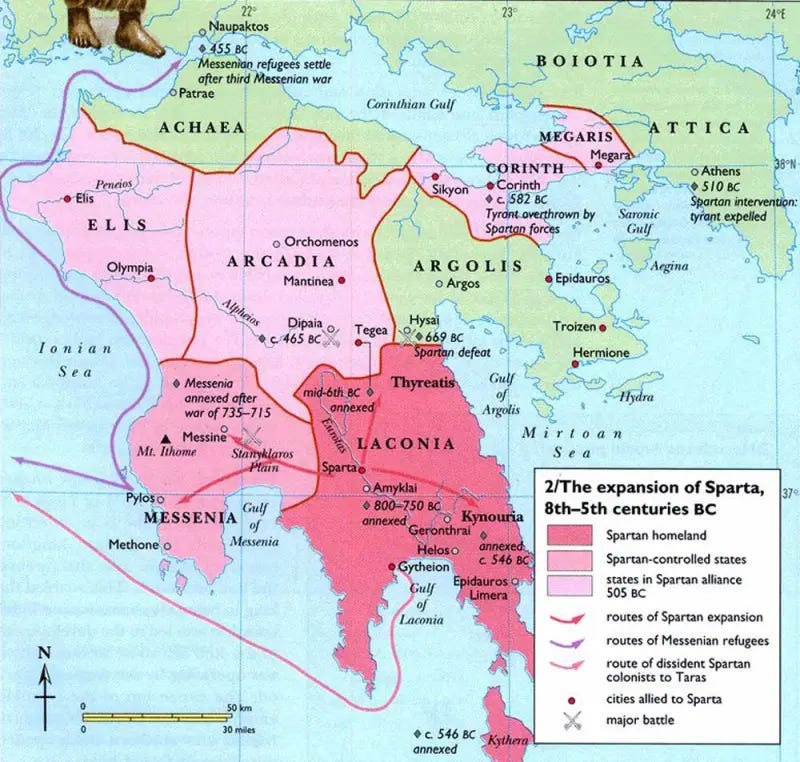

The Spartans are justly legendary—their military prowess was famous in ancient Greece, and they won fame for their many victories in battle and even for their most famous defeat at Thermopylae. Their military strength derived largely from the fact that they were a professional army at a time when most Greek states possessed only amateur militias. The Greek phalanx was not a particularly difficult infantry formation to use, but the Spartans were able to practice a lot, which enabled them to make the formation far more effective and dangerous than other states were able to do. Sparta’s citizens were able to train as professional soldiers because of its conquest of the neighboring region of Messenia in the late eighth and seventh centuries BC. Conquering the region and enslaving its population became the economic advantage that gave Sparta’s citizens the time they needed to train their army. So the conquest of Messenia was largely responsible for Sparta’s great strength, but time after time, it also proved to be Sparta’s great weakness.

While our knowledge of that early period is limited, it seems that growing population pressures drove the Spartans to conquer the Messenia in two separate wars in the late eighth and seventh centuries. This was fairly unusual: Greek states in that period normally dealt with population pressures by establishing overseas colonies to provide new land for excess citizens, so Sparta’s decision to conquer and annex a very large neighboring territory was unusual for that time. The Spartans reduced the entire population of Messenia to slavery, making Sparta the largest enslaver of fellow-Greeks in Greece. The Spartans referred to the enslaved as helots, and possessing such a vast number of enslaved laborers was a great economic benefit to them, since the helots were forced to do all the agricultural labor both in Messenia and in Sparta’s home territory of Laconia. This relieved the Spartans of the need to do agricultural labor themselves, but it also presented them with a serious problem: how to keep control of such a large population of enslaved persons, and how to keep them suppressed and incapable of revolt? How could they keep their massive population of enslaved Greeks from turning on them?

They solved this in two ways. First, they used their freedom from agricultural work to train their citizens and turn them into a fearsome army. Leaving the enslaved helots to toil in fields, Spartan men and boys had the free time to train for war, developing and maintaining a professional army capable of defending Sparta from its own slave population. That army was also used to fight foreign foes and cow nearby states into submission, but the Spartans preferred to keep their army at home to protect their own people from helot uprisings. So it was the freedom from agricultural labor made possible by the mass enslavement of the Messenians that made Spartan military training possible. Second, as part of their military training, Spartan teenagers were often sent into Messenia alone, and armed only with a dagger they were to live off the land and spend their time assassinating all Messenian men who seems likely to cause trouble (these teenagers were called the krypteia). Such terror tactics were intended to keep the enslaved population suppressed and afraid to rebel.

It was therefore the labor of the Messenian helots that enabled the Spartans to spend their days training for war, but this arrangement also had some serious downsides, and often proved to be Sparta’s weak spot or its Achilles’ heel. In the first place, the presence of so many enslaved Messenians eager for freedom meant Sparta’s army could not be away from home for long periods, which limited Sparta’s ability to use that exceptional army. For example, in 499 BC the Greek states in Asia Minor had started a revolt against their Persian overlords and sought help from Sparta, but the Spartans refused when they learned how far away the Greek uprising war. Officially, the Spartans said they needed to stay home because they were more concerned about the activities of their powerful rival Argos, but their real concern seems to have been that giving aid to the eastern Greeks would mean sending Sparta’s army to Asia Minor, which meant the army would be away from Laconia for many, many months. When they realized this, they refused to help and suggested the eastern Greeks approach the Athenians for aid. The Spartans no doubt feared that if their army was gone for such a long period, it would return to find that their city had been burned to the ground by its own enslaved population.

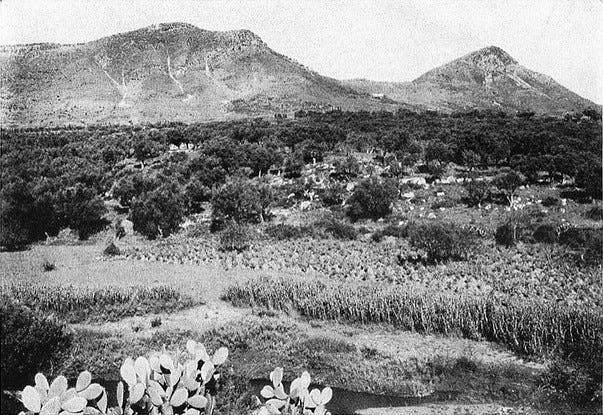

Mt. Ithome

Three occasions show the types of challenges the Spartans faced for holding the Messenians in slavery. First, when an earthquake struck Greece in 464 BC, the helots used the natural phenomenon to start a major uprising against the Spartans. They flocked to Mt. Ithome and used it as a base for their rebellion. The heights of Mt. Ithome have large flat areas perfect for accommodating a large army, but the steep sides of the mountain offer a powerful defense against any attacking army. The Spartans were terrified by the threat this uprising presented, but they had no experience in siege warfare of this type and so did not know how to deal with the rebellious helots secure on their mountaintop. They called for help from their allies and in particular from Athens, which had been developing the arts of naval warfare and so had experience with innovative military tactics. Since the two states were on fairly good terms at that moment, the Athenians sent a large force to help the Spartans. The Athenian army arrived, but very quickly the Spartans became alarmed at the democratic ideas being voiced by the Athenian soldiers. Sparta was very oligarchic and had little interest in democracy, and its leaders became concerned that their subjects and other allies would be won over by the democratic ideals of the Athenians. Afraid that democracy might spread, the Spartans decided to send the Athenian army home immediately, so they summarily—and insultingly—dismissed it from the siege and told it to leave Spartan territory. Angered by such offensive treatment from those who had sought their aid, the Athenians would come to have a change of heart about the plight of the helots on Mt. Ithome….

Mt. Ithome

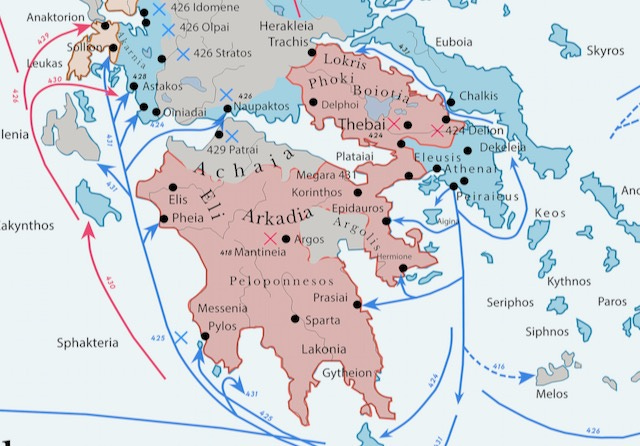

As the siege dragged on and the Spartans were unable to dislodge the rebellious Messenians, they was forced to offer a deal: they would give the army on Ithome safe conduct out of Spartan territory so long as they left and never returned. They were so afraid that the uprising would spread throughout Messenia that they were willing to allow those currently under arms to leave. The helot army agreed, but instead of marching north (the way out of Spartan-controlled Messenia), it marched west to the coast where—to Sparta’s horror—the Athenian fleet was waiting to pick up the now-free Messenians and transport them elsewhere. The Athenians had been so insulted by the treatment they received from Sparta that they picked up the Messenian army and transported it to an Athenian naval base on the north coast of the Gulf of Corinth called Naupactus. The Athenian intervention was an insult to Sparta, but it was also a threat. Naupactus was well positioned to attack and even shut down merchant traffic going in and out of Corinth, which was one of Sparta’s most important allies. Those Messenians at Naupactus held a special hatred for Sparta given the long enslavement of their people, and from their naval base they would prove to be a constant thorn in the sides of both Sparta and Corinth.

Map showing Pylos (SW corner) and Naupactus (in the Gulf of Corinth)

When Athens and Sparta finally found themselves at war with each other in the Peloponnesian War, the helots would be a constant worry for Sparta, since any uprising would be far worse during a time of war. In 425 BC the Athenians sought to use the helots’ hatred for Sparta to their advantage, and they quickly established a naval base at Pylos in Messenia (see map above). According to Homer, Pylos had once been the kingdom of the wise old king Nestor, but the Athenians saw that a seaside fortress there could be easily supplied by the Athenian navy, and thus would be impervious to land attack by the Spartan army. More important, an Athenian base in Messenia offered a refuge to Sparta’s enslaved helots, and those brave enough to flee captivity and could join the Athenians at Pylos and aid their attacks against the Spartans. Indeed, vengeful Messenians were more terrifying to the Spartans than were the Athenians. The Spartans immediately recognized the seriousness of the threat, guessing that the Athenians intended to induce the helots to revolt and cause widespread uprisings throughout Messenia. So the Spartans sent their army to Pylos and did everything they could to dislodge the Athenians from their fortress, but to no avail. Indeed 120 elite Spartan soldiers were captured in the attempt—the first time in recorded history that a Spartan force surrendered. The loss of those soldiers and the fear that the Athenians would whip up widespread revolts of helots drove the Spartans to negotiate a peace treaty with Athens in 421 BC, and they were willing to betray their allies and give a great deal to get the Athenians out of Messenia and away from their masses of enslaved laborers.

The hilltop where the Athenians built their fortress at Pylos

Just as conquering Messenia had enabled the growth of Spartan power, the loss of Messenia was a mortal blow that crushed Spartan power. Sparta had won the Peloponnesian War against Athens, its victory came at a tremendous cost, since it had lost a staggeringly high percentage of its adult male population. In contrast, the city of Thebes emerged from the war with greatly enhanced strength and power. Thebes and Sparta had been allies against Athens, but the course of the war had left Thebes much stronger and Sparta much weaker. As a result, Sparta came to fear its one-time ally, and relations between them rapidly deteriorated. In 371 BC Sparta attempted to get the situation under control by marching its army north and fighting the Theban army on the plain of Leuctra. In this famous battle the Theban commander Epaminondas used innovative tactics to crush the Spartans utterly, marking the first time in the Classical Era that Sparta was soundly and decisively defeated in a major phalanx battle.

Creative on the battlefield, the Theban Epaminondas also had a good understanding of Sparta. He followed up his victory by marching south into Messenia and liberating the entire region from Spartan control. The defeat at Leuctra had left the Spartans too weak to respond, so Epaminondas freed all the Messenians from slavery and built several cities for them to be centers of commerce and military organization. Most important, he helped them build the city of Messene, equipping it with powerful fortifications capable of resisting attacks from Sparta. Thus Epaminondas stripped Sparta of its primary source of wealth and labor, and he created new cities that would check Spartan ambition in the future.

Map showing city of Messene

The loss of Messenia was only one of the social, political, and economic crises that Sparta was experiencing in the mid-fourth century, but it was a particularly decisive loss to Spartan power. Epaminondas and the Thebans attacked again in 362 BC at the second Battle of Mantinea, and the Spartans once again lost, although the death of Epaminondas in that battle caused the Thebans to withdraw without razing Sparta to the ground. When Philip II of Macedon defeated Thebes and Athens at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC, Sparta was the only state that refused to recognize him as the new leader or hegemon of Greece. Yet Philip simply ignored Sparta’s defiance, not because he was afraid of them, but because the Spartans had become weak and powerless without Messenia. Possessing Messenia had enabled Sparta to build its famous army, but losing Messenia left Sparta a weak state that Philip could ignore.

So Sparta was indeed a mighty state with a famous army, but its reliance on its enslaved population was both a great advantage and a great weakness.

Map showing Philip II’s conquests, ignoring Sparta

We’ve heard such a romanticised version of Sparta and Spartans over time that we miss that they’re like any other military nation - doomed by their own insecurities and frailties. Their moment in history is defined by one battle at Thermopylae (justifiably perhaps) while their neighbours and fellow Greeks from the north in Athens claimed their rightful seat in history as the dominant representatives of Greek civilisation via being more progressive, inclusive and assimilative.

Everything comes to an end however when faced with the might of time!

Didn’t Spartans also declare war on helots every year to keep them cowed and permanently terrified?